OHBM2022 Poster and Supplementary Information from metaBIO researchers!

Hello, you probably got here from the QR code on our OHBM2022 poster. Welcome! If not, you are welcome too :D

Short Abstract:

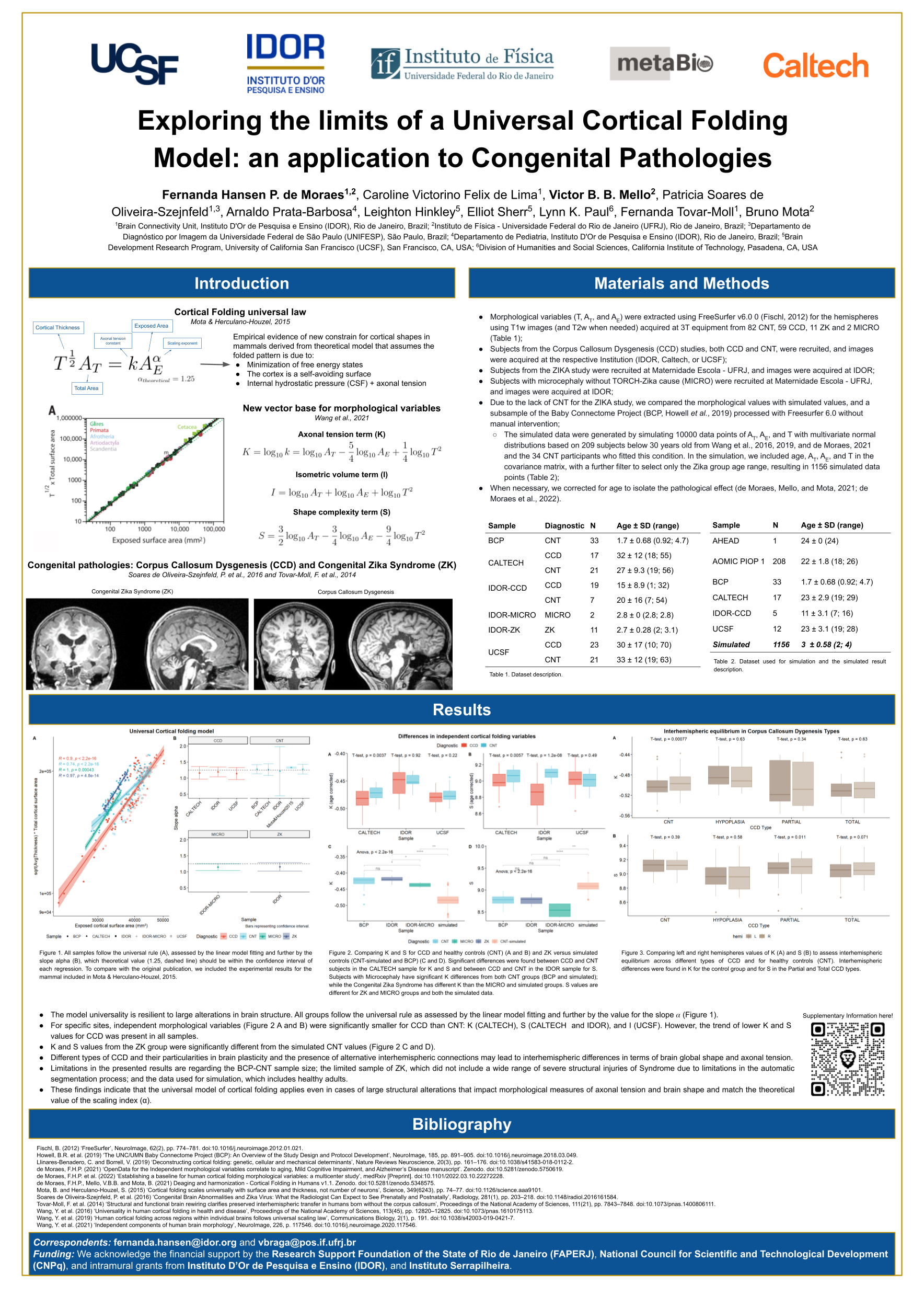

In this work, we explored the limits of a Universal Cortical Folding Model by applying it to Congenital Pathologies, which was proposed by Mota & Herculano-Houzel in 2015. They provided a theory for cortical folding based on physical principles. Empirical evidence of this theory is found for more than 50 mammals is a power-law relation of cortical thickness and areas and leads to a constrain in cortical folding. From that assumption, mammals’ cortices must follow this power-law relation, including human cortices. We then explored how congenital pathologies that can lead to extreme brain structural alterations behave in this model and the vector base derived from it. This new vector base represents three aspects of cortical folding, the axonal tension term K, the isometric volume I, and the shape complexity term S. We selected 82 healthy controls, 59 subjects with Corpus Callosum Dysgenesis, 11 subjects with Zika Congenital Syndrome (ZK), and two subjects with microcephaly without TORCH-Zika cause. Individuals with CCD were born with an atrophied or non-existent Corpus Callosum. In ZK, injuries to brain structure vary according to the disease severity and prenatal age at exposure, with most severe cases exhibiting microcephaly and lissencephaly-like cortices. We conclude from the presented preliminary results that the universal model of cortical folding applies even in cases of extensive structural alterations that impact morphological measures of axonal tension and brain shape and match the theoretical value of the scaling index (α).

Supplementary Information for the work “Exploring the limits of a Universal Cortical Folding Model: an application to Congenital Pathologies” from Fernanda Hansen P. de Moraes1,2,3, Caroline Victorino Felix de Lima1, Victor B. B. Mello2,3, Patricia Soares de Oliveira-Szejnfeld1,4, Arnaldo Prata-Barbosa5, Leighton Hinkley6, Elliot Sherr6, Lynn K. Paul7, Fernanda Tovar-Moll1, Bruno Mota2.

We want to include some additional information regarding the presented research. This will be divided into topics: 1) Previous findings by applying the cortical folding rule in humans; 2) Description of Corpus Callosum Dysgenesis and Congenital Zika Syndrom; 3) Simulated data used; and 4) Limitations.

Previous findings by applying the cortical folding rule in humans (giving the context of what we know by far)

In the last years a few publications explored the Mota & Herculano-Houzel cortical folding model (Mota and Herculano-Houzel 2015) and its derived variables in humans (Wang et al. 2021). What we know:

- The cortical folding model is valid for multiple subjects of one specie, even when accounted for differences in sexes, age, and some pathologies (Wang et al. 2016);

- The model is valid for the hemispheres and lobes (Wang et al. 2019);

- The empirical self-similarity slope reaches the theoretical value for healthy teens and adults (de Moraes et al. 2022);

- The use of K, S, and I allows the characterization of brain morphology naturally, and might further help distinguish similar events (as aging and neurodegeneration) (de Moraes 2021b; Wang et al. 2016; 2021);

- There is a reduction of K (indicating reduced cortical folding) with age;

- There is also a reduction of K, in an accelerated or premature form, in Alzheimer’s Disease (pathological neurodegeneration) (de Moraes 2021b; de Moraes et al. 2022; Wang et al. 2016);

- Alterations in cortical folding (K) have been correlated with alterations in dementia CSF biomarkers and cognitive assessments (de Moraes 2021b).

Description of Corpus Callosum Dysgenesis and Congenital Zika Syndrom

Corpus Callosum Dysgenesis

“Developmental malformations (dysgenesis) of the corpus callosum (CCD) lead to neurological conditions with a broad range of clinical presentations, from entirely asymptomatic to severely handicapped subjects (1). In addition, CCD subjects often fit into the autism spectrum (1,2). When not linked to embryonically lethal causes, CCD usually falls into one of three different phenotypes: complete dysgenesis, also known as agenesis (CA); partial dysgenesis, which preserves a small remnant of the corpus callosum (CC; usually the genu); and hypoplasia (HP), with an anatomically typical but shortened CC (1,3). Although previous studies described the heterogeneous anatomical phenotypes of CCD patients and their neuropsychological presentations, the relationship between the altered structural brain wiring in CCD and the subsequent adaptive and maladaptive functional connectivity changes is still a subject of active research (3,4).” (direct citation from Szczupak et al. 2021)

For an extensive review, please see (Paul et al. 2007).

Congenital Zika Syndrom

The Brazilian ZIKV epidemic began in late 2015 and quickly drew worldwide attention. In 2016, the World Health Organization declared ZIKV infection epidemics a public health threat of international concern, specifically because of their association with fetal/neonatal microcephaly and other neurodevelopment anomalies.

Brains of fetuses and neonates with CZS are characterized by neurodevelopmental malformations, in multiple severities. Although imaging and clinical findings are not specific to ZIKV, some findings were very common and highly prevalent in several reported studies with different cohorts. Among the most striking findings were microcephaly, gyral simplification, including pachygyria and agyria, hydrocephalus with hypoplastic brainstem and aqueduct stenosis, ribbon cortical/subcortical calcification, cortical dysplasia, cortical development abnormalities, hypoplastic or dysgenesis of the corpus callosum, arthrogryposis and anterior spinal cord malformation (Soares de Oliveira-Szejnfeld et al. 2016; Melo et al. 2016; Chimelli et al. 2017).

Simulated data used

We simulated data using subjects below 30 years from (de Moraes 2021; Wang et al. 2019), a subsample of the Baby Connectome Project (BCP) (Howell et al. 2019), and 34 CNT participants who fitted this condition. We generated 10000 data points of AT, AE, and T a covariance matrix of AT, AE, T, and Age to account for the dependence within those variables. We further filtered the generated data to the age range of the ZK and MICRO groups (2; 3.1 years old) (Table 1).

| Sample | N | Age ± SD (range) |

|---|---|---|

| AHEAD | 1 | 24 ± 0 (24) |

| AOMIC PIOP 1 | 208 | 22 ± 1.8 (18; 26) |

| BCP | 33 | 1.7 ± 0.68 (0.92; 4.7) |

| CALTECH | 17 | 23 ± 2.9 (19; 29) |

| IDOR-CCD | 5 | 11 ± 3.1 (7; 16) |

| UCSF | 12 | 23 ± 3.1 (19; 28) |

| Simulated | 1156 | 3 ± 0.58 (2; 4) |

Table 1. Dataset used for simulation and the simulated result description.

To ensure the simulated data was adequate, we applied the cortical folding model. The simulated data fitted the linear model with R2 = 0.87, p < 0.0001 and self-similarity exponent of 1.25 (95% CI 1.23; 1.28) (Figure 1).

Figure 1. The cortical folding model and the simulated data. The blue line represents the linear regression of the simulated data, while the red line is the linear regression of true data used as a reference for the simulation, and the dashed red lines represent the confidence interval of the true regression.

Limitations

We intended here to provide preliminary results from an incipient study relating congenital pathologies and cortical folding. Thus we still have some limitations to overcome.

Due to the inherent characteristics of these pathologies that might lead to extreme alterations in brain structure, our image processing pipeline is not optimal8. To overcome this limitation, and not include more uncertainties due to manually correcting surfaces from all subjects (including the ones that it was not necessary), we intend to correct subjects under the supervision of an experient radiologist, and only those with extensive surface errors. Also, without the correction, the surfaces could disguise differences, for example, between DCC types, as it might not have been sensible enough to the anatomical differences across our heterogenic sample. The processing limitation is also true for the BCP sample, in which only a subsample is processed and went under visual inspection. We expect to include all subjects from the sample in future presentations of this study.

Our second main limitation is related to the simulated sample. We simulated data using linear functions of T, AT, AE extracted from 0 to 30 years old, including them, adults. This is probably not the optimal methodology, but the one workable within this context and sample size. We expect to improve those linear functions by including more subjects, as an expansion of our previous work (de Moraes et al. 2022).

Bibliography

Chimelli, Leila, Adriana S. O. Melo, Elyzabeth Avvad-Portari, Clayton A. Wiley, Aline H. S. Camacho, Vania S. Lopes, Heloisa N. Machado, et al. 2017. “The Spectrum of Neuropathological Changes Associated with Congenital Zika Virus Infection.” Acta Neuropathologica 133 (6): 983–99. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00401-017-1699-5.

Howell, Brittany R., Martin A. Styner, Wei Gao, Pew-Thian Yap, Li Wang, Kristine Baluyot, Essa Yacoub, et al. 2019. “The UNC/UMN Baby Connectome Project (BCP): An Overview of the Study Design and Protocol Development.” NeuroImage 185 (January): 891–905. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neuroimage.2018.03.049.

Kliemann, Dorit, Ralph Adolphs, Tim Armstrong, Paola Galdi, David A. Kahn, Tessa Rusch, A. Zeynep Enkavi, et al. 2022. “Caltech Conte Center, a Multimodal Data Resource for Exploring Social Cognition and Decision-Making.” Scientific Data 9 (1): 138. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41597-022-01171-2.

Melo, Adriana Suely de Oliveira, Renato Santana Aguiar, Melania Maria Ramos Amorim, Monica B. Arruda, Fabiana de Oliveira Melo, Suelem Taís Clementino Ribeiro, Alba Gean Medeiros Batista, et al. 2016. “Congenital Zika Virus Infection: Beyond Neonatal Microcephaly.” JAMA Neurology 73 (12): 1407–16. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamaneurol.2016.3720.

de Moraes, Fernanda Hansen Pacheco. 2021a. “OpenData for the Independent Morphological Variables Correlate to Aging, Mild Cognitive Impairment, and Alzheimer’s Disease Manuscript.” Zenodo. https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.5750619.

———. 2021b. Independent Morphological Variables Correlate to Aging, Mild Cognitive Impairment, and Alzheimer’s Disease - Analysis Code (version 0.1). FHPdeMoraes_thesis. https://github.com/metaBIOlab/FHPdeMoraes_thesis. https://github.com/metaBIOlab/FHPdeMoraes_thesis.

de Moraes, Fernanda Hansen Pacheco, Victor B. B. Mello, Fernanda Tovar-Moll, and Bruno Mota. 2022. “Establishing a Baseline for Human Cortical Folding Morphological Variables: A Multicenter Study.” MedRxiv. https://doi.org/10.1101/2022.03.10.22272228.

Mota, Bruno, and Suzana Herculano-Houzel. 2015. “Cortical Folding Scales Universally with Surface Area and Thickness, Not Number of Neurons.” Science 349 (6243): 74–77. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.aaa9101.

Paul, Lynn K., Warren S. Brown, Ralph Adolphs, J. Michael Tyszka, Linda J. Richards, Pratik Mukherjee, and Elliott H. Sherr. 2007. “Agenesis of the Corpus Callosum: Genetic, Developmental and Functional Aspects of Connectivity.” Nature Reviews Neuroscience 8 (4): 287–99. https://doi.org/10.1038/nrn2107.

Soares de Oliveira-Szejnfeld, Patricia, Deborah Levine, Adriana Suely de Oliveira Melo, Melania Maria Ramos Amorim, Alba Gean M. Batista, Leila Chimelli, Amilcar Tanuri, et al. 2016. “Congenital Brain Abnormalities and Zika Virus: What the Radiologist Can Expect to See Prenatally and Postnatally.” Radiology 281 (1): 203–18. https://doi.org/10.1148/radiol.2016161584.

Szczupak, Diego, Marina Kossmann Ferraz, Lucas Gemal, Patricia S Oliveira-Szejnfeld, Myriam Monteiro, Ivanei Bramati, Fernando R Vargas, et al. 2021. “Corpus Callosum Dysgenesis Causes Novel Patterns of Structural and Functional Brain Connectivity.” Brain Communications 3 (2): fcab057. https://doi.org/10.1093/braincomms/fcab057.

Wang, Yujiang, Karoline Leiberg, Tobias Ludwig, Bethany Little, Joe H Necus, Gavin Winston, Sjoerd B Vos, et al. 2021. “Independent Components of Human Brain Morphology.” NeuroImage 226 (February): 117546. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neuroimage.2020.117546.

Wang, Yujiang, Joe Necus, Marcus Kaiser, and Bruno Mota. 2016. “Universality in Human Cortical Folding in Health and Disease.” Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 113 (45): 12820–25. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1610175113.

Wang, Yujiang, Joe Necus, Luis Peraza Rodriguez, Peter Neal Taylor, and Bruno Mota. 2019. “Human Cortical Folding across Regions within Individual Brains Follows Universal Scaling Law.” Communications Biology 2 (1): 191. https://doi.org/10.1038/s42003-019-0421-7.

Footnotes

-

Brain Connectivity Unit, Instituto D’Or de Pesquisa e Ensino (IDOR), Rio de Janeiro, Brazil ↩ ↩2 ↩3 ↩4

-

Instituto de Física - Universidade Federal do Rio de Janeiro (UFRJ), Rio de Janeiro, Brazil ↩ ↩2 ↩3

-

Presenting in person in Glasgow :D and correspondents: fernanda.hansen@idor.org and vbraga@pos.if.ufrj.br ↩ ↩2

-

Departamento de Diagnóstico por Imagem da Universidade Federal de São Paulo (UNIFESP), São Paulo, Brazil ↩

-

Departamento de Pediatria, Instituto D’Or de Pesquisa e Ensino (IDOR), Rio de Janeiro, Brazil ↩

-

Brain Development Research Program, University of California San Francisco (UCSF), San Francisco, CA, USA ↩ ↩2

-

Division of Humanities and Social Sciences, California Institute of Technology, Pasadena, CA, USA ↩

-

Kliemann et al. 2022 recently described limitations in FreeSurfer automatic tracing and examples of needed manual edition for healthy individuals in the Caltech Conte Center, what give us a red alarm in neuroatypical subjects with major alterations in brain structure. ↩